So, we're behind on the blog this week. This is pretty much entirely my fault. We're going to be shifting to stories from Manuel's life for a bit, which I'm really excited about because the dude has some amazing stories. But I'm way behind on typing them up. I haven't even sent a draft Manuel's way yet for this week's story, so I suppose it's wise to just admit we're taking an off week.

However, I have a wee vignette to share. It's not really visual enough to have Manuel draw but it's one of those brief chance meetings that stuck out for me.

--------

My birthday is the day after Christmas. I turned 29 a few weeks ago, and I celebrated with a bunch of great friends at a couple bars in North Beach, across town from where I live, in the Excelsior. This is a cutty neighborhood, way out at the end of the city. If I mention to people I live there, six times out of ten they ask, "Where?" And that's people who also live in San Francisco.

Anyway, I called a cab to get me to the bar. I was by myself, meeting some people there, but the cab that showed up was one of those big van cabs.

Well, that was pretty cool. I smiled to myself that I got to stretch out in this nice big van the whole way across town and sidled on in.

The cab driver was this blonde lady, with real short hair, maybe 45 or 50 years old. She seemed confused at first and had a hard time figuring out her way to the freeway.

After I talked her to the on ramp, I asked her, "How long have you been a cab driver?" I was curious if she was disoriented because she was new at driving around the city or because I lived in the boonies.

"About... a year and one half," she said. She had a striking Russian accent -- it was just a tiny bit husky, but still feminine and ornate. There was kind of a baroque trill to her sharp consonants and I realized I hadn't heard such a beautiful Russian accent in a long time. Usually the Russian accents I hear are shouted on the bus and sound like a German is throwing up while trying to remember song lyrics.

So, it turned out she was a bookkeeper who'd moved to San Francisco some ten years or so back to be with her family, "because it became very lonely for me in Moscow."

She'd done accounting for a jewelry dealer for many years, and when he moved his business up to Portland he offered her a job there, but she declined because she only lived in the States to get closer to her family.

They'd all emigrated here, I learned, but her. She had stayed in Moscow to be with her husband, who died.

She very much liked accounting and was good at it, but the economy made a new job in her field seem out of reach, so she took up the taxi to make ends meet.

"I like to drive," she said. "I am very good driver, but every day I thank God. I have no accidents and no crashes. Is amazing, if you drive so much, to have no accidents."

Later, in the midst of a shortcut she was excited to show me, we got stuck dead in traffic while the crowd from a ball game crossed the streets downtown. She apologized profusely.

"I am very fast," she said, "but there is nothing to do here."

Finally, having gotten to know her a bit, I complimented her accent. She held a hand to her mouth as if daintily blocking a little burp.

"I am embarrassed by it," she said. "I am here ten years and it doesn't go away. It sounds like pornography, like four-letter words."

Well, I liked it, I told her.

Nearing the bar, she got around to explaining why she was so afraid of accidents. Her husband had been driving in Moscow and was sideswiped by a car that left him completely paralyzed.

"I lived to care for him for three years and then he died," she said. "They said get a nurse or put him in a hospital, but no. I cared for him."

She must have really loved him, I said. We were at a stoplight. She put her arm over the shotgun seat and turned around to look at me, and she said:

"He was very nice man."

The whole ride was just great. Her name, I found out moments before leaving the cab, was Nina. I liked Nina. I liked how simple she felt the situations of her life had been, how in spite of being deeply difficult, their demands had at least been clear.

But maybe my favorite thing was something she said after I brought up her accent. She'd been here ten years, yes, and she spoke English now, but when she first arrived she didn't know a word of it. She stayed with her family and went to school.

In her first weeks in the city, she went for walks, she said, and one day she saw a man walking his dog. She saw the man order the dog to sit, and watched the dog sit. Stay, and the dog stayed. Heel, and the dog heeled.

"And I remember thinking I am jealous of that dog," she said, "for he understands English, and I have none."

Follow the Blog:

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

Monday, January 11, 2010

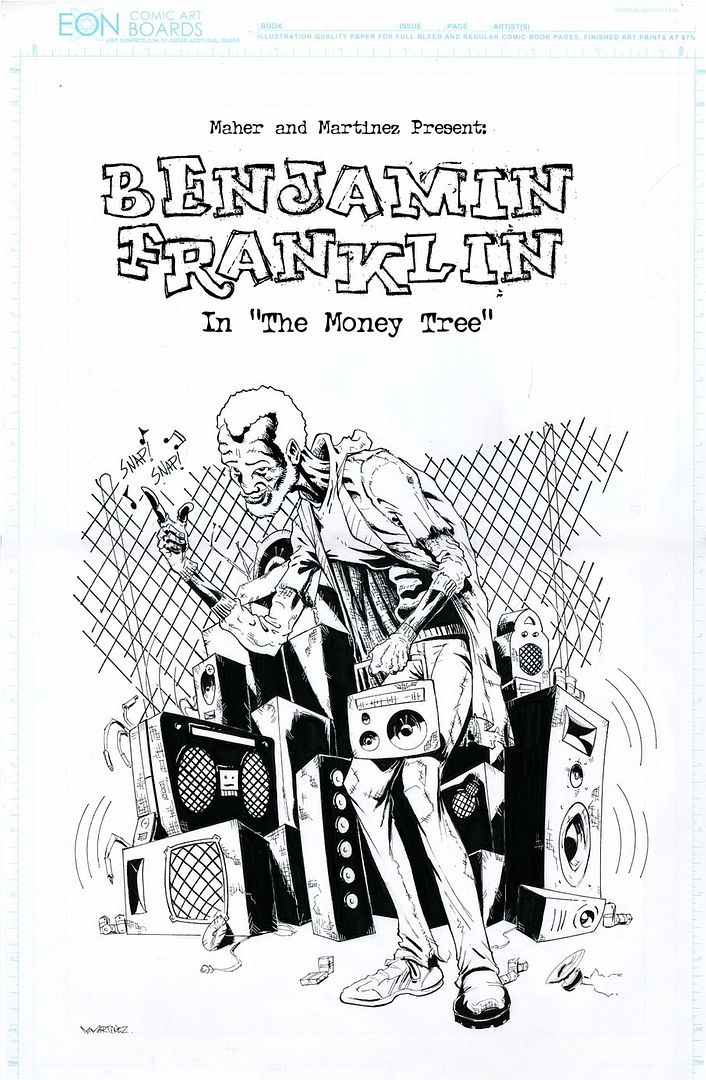

Benjamin Franklin: The Homeless Stereo King

I met Benjamin Franklin as I was walking to Safeway ten years ago on a lunch break from my first real job. I was working for the San Francisco Design Center, a giant high-end interior design mall for rich people. One ironic thing about the place was that it was surrounded by some of the poorest streets in the city. The bus to work was full of homeless people and drug addicts and morbidly obese men and women in wheelchairs and dressed up blondes and gay guys on their way to work in the Design Center’s showrooms.

Me, I was learning how to do office work, planning events, getting screamed at by Louis, the psycho in accounting. I was also looking superfly in my black fur-felt fedora. I grew up stoked on old movies with Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney going around acting like badasses in hats. I thought men looked awesome in hats ever since, so I bought one with my first paycheck at my first-ever job, clerking at a video store. As much of an affectation as it was, I didn’t give a shit: I loved that hat.

So one day for lunch I was walking up to Potrero Boulevard, one of the liveliest, poorest streets in that part of the city, and I saw the Homeless Stereo King.

He was a tall, gangly kind of guy, but permanently bent and bobbing along with the music. Up against the chain link fence behind him was a pyramid of stereo equipment four or five feet tall: boom boxes, Discmans, Walkmans, busted-up speakers, radios. On the side of that was a shopping cart ALSO full of boom boxes and radios, but also with cassette tapes and empty battery packages and cracked CD cases.

The man in charge of this unbelievable cache of music machines had a tape running at top volume in one of the smaller boom boxes, playing some trumpety 70s funk as loud as its tiny tinny speakers could fuzz out. The man was swaying and laughing to himself, running his own personal, mellow dance party. He wasn’t flinging himself all over the place, just bumping side to side in a one-man, open-to-the-public groove.

I came walking up and, getting a fun vibe from the music and encouraged by a smile from this old guy, I bounced my shoulders and strutted a little.

“Well, look who’s here!” the guy said in a throaty, Creole accent. “It’s David Booway!”

I was so happy to be called David Bowie, and in an awesome accent, that I stopped and threw the guy a handshake. It completely made my day.

“What’s going on today, my man?” I asked.

“Oh, I’m just feeling love, brother, you know.”

“What’s your name, friend?”

“Ah, well y’see, MY name… is, ah… Benjamin Franklin,” he said, and he laughed this soft, wheezing laugh, as if he were getting away with something. I thought he was fucking with me.

“Did you just tell me your name is Benjamin Franklin?” I said.

“Yeah, baby, I AM Benjamin Franklin. Hoo, yah!”

Hell, if that’s what he wanted me to call him, that’s what I’d call him.

So we talked about music for a few minutes and then I headed off to buy some lunch. He didn’t ask me for any money, which was a relief. We’d had a fun conversation, and too often with San Francisco homeless people you find in the end it was basically an extended transaction. To have the conversation actually be just a conversation, just two people getting to know each other by talking, was really pretty cool to me.

I went back that way again a few days later and Benjamin Franklin was still there, this time with a different boom box playing, and we laughed and danced a little and I walked on to get my lunch. It ended up being something I did two or three times a week, just because the guy always made me smile. He was crazy, but something about it was okay: he didn’t seem lonely or sad, or even too upset about being so poor.

He never asked me for money, and he usually politely turned down any food I offered. The soup kitchen was right around the corner, after all. But once I came walking up and there was no music playing – he just leaned against the fence, not morose but clearly a little bummed.

“What’s going on, Benjamin Franklin?” I asked. He always called me by my full name (“Hey, look, it’s David Booway too-day! That’s a beautiful hat you got there, David Booway!”) so I always called him by his. And if he was conning me about the name, which seemed possible because every time I called him that he got that same mischievous, toothy grin on his face, I didn’t really care.

“Aw, baby, my batteries is all died,” he said. He turned to me with an almost conspiratorial, looking-over-his-shoulder posture, holding out a dirt-stained little tape player, and he said, “If it ain’t too much trouble, if you could bring me back some batteries from that Safeway, I could put ‘em in here and we rockin’ again.”

“Shit yeah, my man, I’ll get you some batteries.” He told me what kind he needed and I got a big pack of ‘em at the Safeway and gave him the handoff on my way back and when I walked by a few days later there he was, music back on, feeling good and dancing by himself.

Sometimes I’d see him with a little bit of money, and that was when I knew he actually was crazy. He’d walk out into the street, to a nearby manhole cover, and he’d jam dollar bills into the holes in the manhole cover. I saw him doing it once and I asked, “Uh, Benjamin Franklin? What the hell are you doing?”

“Aw, I’m planting that shit, baby.”

“Planting it?”

“Yeah, baby, planting that shit. Gone grow something.”

“…”

Well, it was harmless enough, I supposed. The guy was clearly able to eat and he seemed to have a place to go at night.

Well, one day in the winter, early in the year, I came walking up on my way to Safeway, and he was missing. The shopping cart and the mountain of stereos were still there, but all by themselves, weirdly still and silent. Something felt creepy about it. I figured he was getting lunch, though, because there was a line outside the soup kitchen, and I went and bought some fried chicken strips at Safeway.

As I walked back, somebody in line at the soup kitchen shouted, “Hey!”

I turned around and looked down the sidewalk.

“Hey! Yeah, you!”

Me?

“Yeah, come here! I gotta tell you something!”

I walked over. I’d never seen this guy in my life, but he seemed pretty clearly to recognize me. I walked up and I asked him what was going on, and he said a sentence to me I don’t think I’ll forget as long as I live:

“Something HORRIBLE happened.”

I actually had to pause a second because it was such a plain, simple, devastating thing to say I didn’t know how to react. But somehow I knew what was coming.

“What ?” I asked.

“That guy, the ol’ dude with the stereos?”

I nodded. And I knew where this was going.

“He got hit by a car, man. He’s gone.”

Turns out Benjamin Franklin was out there at the manhole cover, planting his money, and someone had driven by, hit him and sailed on, leaving a crazy old homeless man battered and dying on the street. By the time an ambulance arrived it was way too late.

I walked back to work in kind of a daze. I stopped at his spot, which now felt more like a shrine. I knew other people would arrive soon like vultures to take whatever they could find to sell for a buck or two, and I didn’t really mind: my friend obviously didn’t need this stuff anymore, and it might as well be of some aid to somebody. But I wanted some kind of memento. I saw a single, recordable cassette tape lying in the kiddie-seat of the shopping cart, and I picked it up and put it in my pocket.

I wasn’t sure how to deal with Benjamin Franklin’s death. When somebody close to you dies, you can go ahead and make a big deal out of it. A family member, a friend from school or work, somebody you spend your downtime with dies? You feel powerfully sad, and you can cry and ask people for space or for support or whatever you want to do. But as much as I liked Benjamin Franklin, as much as I enjoyed him and liked getting him batteries when he was out, he wasn’t that kind of person in my life. I was mournful for him, but I didn’t feel grief, and I didn’t want to do anything disrespectful or phony with his death.

I talked about it with Molly and Darren, who was living in San Francisco then. I showed them the tape and I explained it was the guy who called me David Booway, and repeated what I’d been told happened. They both gave me condolences but I paused and told them I wasn’t looking for sympathy, and explained the weird feedback loop I had going on in my head.

Darren thought about it a moment and said:

“Well, I guess you should just keep the tape, and then every once in a while you can tell somebody about him. And that way people will know who he was, and maybe that’s the best thing you can do for him.”

It felt like one of the simplest, wisest pieces of advice I’d ever gotten. And I followed it. And I’m following it now.

Benjamin Franklin, ladies and gentlemen. On behalf of Manuel and myself, for whom the acts of storytelling and audience are so personal and so important, thank you for reading about him, and thinking of him.

Words: Sean Murray

Art: Manuel Martinez

Me, I was learning how to do office work, planning events, getting screamed at by Louis, the psycho in accounting. I was also looking superfly in my black fur-felt fedora. I grew up stoked on old movies with Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney going around acting like badasses in hats. I thought men looked awesome in hats ever since, so I bought one with my first paycheck at my first-ever job, clerking at a video store. As much of an affectation as it was, I didn’t give a shit: I loved that hat.

So one day for lunch I was walking up to Potrero Boulevard, one of the liveliest, poorest streets in that part of the city, and I saw the Homeless Stereo King.

He was a tall, gangly kind of guy, but permanently bent and bobbing along with the music. Up against the chain link fence behind him was a pyramid of stereo equipment four or five feet tall: boom boxes, Discmans, Walkmans, busted-up speakers, radios. On the side of that was a shopping cart ALSO full of boom boxes and radios, but also with cassette tapes and empty battery packages and cracked CD cases.

The man in charge of this unbelievable cache of music machines had a tape running at top volume in one of the smaller boom boxes, playing some trumpety 70s funk as loud as its tiny tinny speakers could fuzz out. The man was swaying and laughing to himself, running his own personal, mellow dance party. He wasn’t flinging himself all over the place, just bumping side to side in a one-man, open-to-the-public groove.

I came walking up and, getting a fun vibe from the music and encouraged by a smile from this old guy, I bounced my shoulders and strutted a little.

“Well, look who’s here!” the guy said in a throaty, Creole accent. “It’s David Booway!”

I was so happy to be called David Bowie, and in an awesome accent, that I stopped and threw the guy a handshake. It completely made my day.

“What’s going on today, my man?” I asked.

“Oh, I’m just feeling love, brother, you know.”

“What’s your name, friend?”

“Ah, well y’see, MY name… is, ah… Benjamin Franklin,” he said, and he laughed this soft, wheezing laugh, as if he were getting away with something. I thought he was fucking with me.

“Did you just tell me your name is Benjamin Franklin?” I said.

“Yeah, baby, I AM Benjamin Franklin. Hoo, yah!”

Hell, if that’s what he wanted me to call him, that’s what I’d call him.

So we talked about music for a few minutes and then I headed off to buy some lunch. He didn’t ask me for any money, which was a relief. We’d had a fun conversation, and too often with San Francisco homeless people you find in the end it was basically an extended transaction. To have the conversation actually be just a conversation, just two people getting to know each other by talking, was really pretty cool to me.

I went back that way again a few days later and Benjamin Franklin was still there, this time with a different boom box playing, and we laughed and danced a little and I walked on to get my lunch. It ended up being something I did two or three times a week, just because the guy always made me smile. He was crazy, but something about it was okay: he didn’t seem lonely or sad, or even too upset about being so poor.

He never asked me for money, and he usually politely turned down any food I offered. The soup kitchen was right around the corner, after all. But once I came walking up and there was no music playing – he just leaned against the fence, not morose but clearly a little bummed.

“What’s going on, Benjamin Franklin?” I asked. He always called me by my full name (“Hey, look, it’s David Booway too-day! That’s a beautiful hat you got there, David Booway!”) so I always called him by his. And if he was conning me about the name, which seemed possible because every time I called him that he got that same mischievous, toothy grin on his face, I didn’t really care.

“Aw, baby, my batteries is all died,” he said. He turned to me with an almost conspiratorial, looking-over-his-shoulder posture, holding out a dirt-stained little tape player, and he said, “If it ain’t too much trouble, if you could bring me back some batteries from that Safeway, I could put ‘em in here and we rockin’ again.”

“Shit yeah, my man, I’ll get you some batteries.” He told me what kind he needed and I got a big pack of ‘em at the Safeway and gave him the handoff on my way back and when I walked by a few days later there he was, music back on, feeling good and dancing by himself.

Sometimes I’d see him with a little bit of money, and that was when I knew he actually was crazy. He’d walk out into the street, to a nearby manhole cover, and he’d jam dollar bills into the holes in the manhole cover. I saw him doing it once and I asked, “Uh, Benjamin Franklin? What the hell are you doing?”

“Aw, I’m planting that shit, baby.”

“Planting it?”

“Yeah, baby, planting that shit. Gone grow something.”

“…”

Well, it was harmless enough, I supposed. The guy was clearly able to eat and he seemed to have a place to go at night.

Well, one day in the winter, early in the year, I came walking up on my way to Safeway, and he was missing. The shopping cart and the mountain of stereos were still there, but all by themselves, weirdly still and silent. Something felt creepy about it. I figured he was getting lunch, though, because there was a line outside the soup kitchen, and I went and bought some fried chicken strips at Safeway.

As I walked back, somebody in line at the soup kitchen shouted, “Hey!”

I turned around and looked down the sidewalk.

“Hey! Yeah, you!”

Me?

“Yeah, come here! I gotta tell you something!”

I walked over. I’d never seen this guy in my life, but he seemed pretty clearly to recognize me. I walked up and I asked him what was going on, and he said a sentence to me I don’t think I’ll forget as long as I live:

“Something HORRIBLE happened.”

I actually had to pause a second because it was such a plain, simple, devastating thing to say I didn’t know how to react. But somehow I knew what was coming.

“What ?” I asked.

“That guy, the ol’ dude with the stereos?”

I nodded. And I knew where this was going.

“He got hit by a car, man. He’s gone.”

Turns out Benjamin Franklin was out there at the manhole cover, planting his money, and someone had driven by, hit him and sailed on, leaving a crazy old homeless man battered and dying on the street. By the time an ambulance arrived it was way too late.

I walked back to work in kind of a daze. I stopped at his spot, which now felt more like a shrine. I knew other people would arrive soon like vultures to take whatever they could find to sell for a buck or two, and I didn’t really mind: my friend obviously didn’t need this stuff anymore, and it might as well be of some aid to somebody. But I wanted some kind of memento. I saw a single, recordable cassette tape lying in the kiddie-seat of the shopping cart, and I picked it up and put it in my pocket.

I wasn’t sure how to deal with Benjamin Franklin’s death. When somebody close to you dies, you can go ahead and make a big deal out of it. A family member, a friend from school or work, somebody you spend your downtime with dies? You feel powerfully sad, and you can cry and ask people for space or for support or whatever you want to do. But as much as I liked Benjamin Franklin, as much as I enjoyed him and liked getting him batteries when he was out, he wasn’t that kind of person in my life. I was mournful for him, but I didn’t feel grief, and I didn’t want to do anything disrespectful or phony with his death.

I talked about it with Molly and Darren, who was living in San Francisco then. I showed them the tape and I explained it was the guy who called me David Booway, and repeated what I’d been told happened. They both gave me condolences but I paused and told them I wasn’t looking for sympathy, and explained the weird feedback loop I had going on in my head.

Darren thought about it a moment and said:

“Well, I guess you should just keep the tape, and then every once in a while you can tell somebody about him. And that way people will know who he was, and maybe that’s the best thing you can do for him.”

It felt like one of the simplest, wisest pieces of advice I’d ever gotten. And I followed it. And I’m following it now.

Benjamin Franklin, ladies and gentlemen. On behalf of Manuel and myself, for whom the acts of storytelling and audience are so personal and so important, thank you for reading about him, and thinking of him.

Words: Sean Murray

Art: Manuel Martinez

Subscribe to:

Comment Feed (RSS)